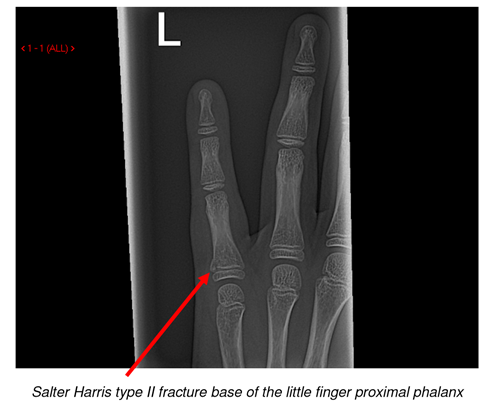

In a comprehensive examination of the 1998 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from US facilities, Chung et al. 3,4 In the UK, a stratified examination found the number of hand fractures per year within the general pediatric population to be low in toddlers (34/100,000 children), and increased nearly 20-fold after the 10th year to 663 hand fractures each year per 100,000 children ages 11-18. 1, 2 In the pediatric population, hand fractures make up 2.3% of all ER visits, and the incidence of these fractures varies significantly by age. Population database studies often use 18 years as a cut-off age for defining these fractures and may overestimate the prevalence of true pediatric hand fractures.įifteen percent of all fractures seen in the ER setting are hand fractures and nearly half of these fractures are a result either of sports activities or fights. Typically, a “pediatric” hand fracture would include children who continue to have open physes and therefore deserve special consideration regarding immobilization, remodeling potential, and surgical indications. Despite the high potential for excellent outcomes in pediatric hand fractures, some fractures remain difficult to diagnose and treat.ĭistinguishing true “pediatric” hand fractures from fractures occurring in skeletally immature children and adolescents can be difficult if using epidemiologic studies only. Following immobilization, children rarely develop hand stiffness and formal occupational therapy is usually not necessary. Most fractures complete bony healing in 3-4 weeks, with the scaphoid being a notable exception. In children, the thick, vascular-rich periosteum and bony remodeling potential make anatomic reductions and internal fixation rarely necessary. Most fractures can be treated operatively with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning if addressed within the first week following the injury. However, fractures may require operative stabilization if they have substantial angulation or rotation, extend into the joint, or cannot be held in a reduced position with splinting alone. If correctly diagnosed, reduced and immobilized, these fractures usually result in excellent clinical outcomes. Most simple fractures can be treated with appropriate immobilization through buddy taping, finger splints, or casting. Identification of the fractures in the emergency room setting can be challenging owing to the physes and incomplete ossification of the carpus that are not revealed in the xrays. Pediatric hand fractures are common childhood injuries.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)